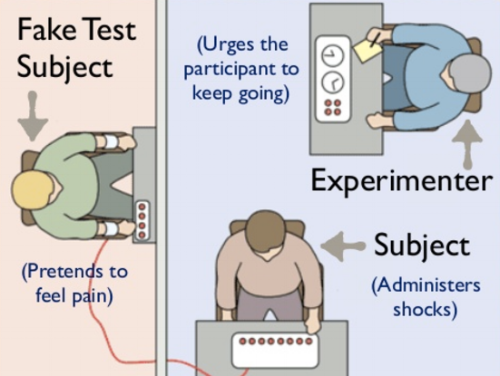

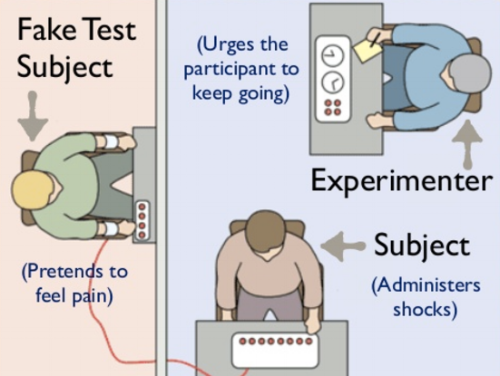

The experiment involved a participant being paired with another person. They drew straws to find out who would assume one of two roles: the ‘learner’ or the ‘teacher’. The learner was taken into a room and had electrodes attached to his arms, while the teacher and a researcher went into a room next door that contained an electric shock generator and a row of switches marked from 15 volts (slight shock) to 450 volts (danger: severe shock).

The teacher would ask a question that the learner should know the answer to and would deliver an electric shock if they did not answer correctly. Milgram told participants that he was investigating the impact of punishment on learning; as such, the teacher was instructed by the researcher to administer shocks of increasing intensity each time the learner provided the wrong answer. If the teacher refused to administer a shock, the researcher would use a sequence of four verbal prods designed to assure the participant that it was important to continue. If, after all four prods, the participant still wished to stop, the experiment would finish.

But of course, there’s a twist: one participant in each pair was actually a scientist and was only pretending to be a participant. The draw was fixed so that the real participant would always be the ‘teacher’, while the scientist would always be the ‘learner’. The true purpose of the experiment was simple: Milgram wanted to see how many people would administer a shock of maximum voltage just because an authority figure told them to do it. The scientists deliberately answered many questions incorrectly and would protest with every “shock”, eventually falling silent after receiving 450 volts. Interestingly, each participant paused to question the safety of the learner, but once reassured by the authority figure, most chose to continue with “shocking” the learner.

If you’d like to see a diagram of the experiment, here’s one:

Image credit: moderntherapy.online

There were several different variants of the experiment including one where the learner supposedly receiving the electric shock was in the same room as the teacher (versus separate rooms as shown above). When in the same room, the teacher was able to experience the learner’s pain more directly; in this set-up, around 40% of participants continued to the highest level shock of 450 volts, which would have been enough to kill the learner. When the learner was further away and in a separate room, the percentage of participants delivering the maximum 450 volt shock increased to 65%.

For a different (but similarly interesting) example, look into the Stanford prison experiment by Philip Zimbardo.

However, there are some interesting conclusions to arise from the research. Drawing from the variations of the experiment discussed above and their application to modern organisations, the research says that individuals are capable of doing harm to another even if that person is in near proximity, but they are significantly more likely to do harm to that other person if they are not close enough to witness that person’s pain directly.

Put another way, there is a difference between a small business owner having to terminate two of their five staff and the board of a multi-national organisation deciding to terminate the jobs of thousands of people they have never met.

That example is probably quite intuitive and maybe even obvious; but what of other decisions that boards make regularly?

In not for profit organisations, how do you weigh the decision of adding a new staff member, whether they are in a corporate position or frontline service delivery? Or when downsizing, which roles go first and how is the impact on customers and individuals considered?

For not for profit, or purpose-led organisations, our focus should always be on the outcomes for our service users. So, we need to keep them front and centre of decision making.

Now that we understand the why, how can we bring the voice of the customer into the boardroom? Here are some suggestions for how to do it:

- Recruit some directors (a percentage of the board) who have some experience of the types of services the organisation provides, or the needs of those affected and impacted by the organisation. With this approach, ensure that any conflict of interest is managed and recognise that these are a sample of customer voices, but they are not representative unless a system is in place for these directors to seek input from other users.

- Use a Customer Reference Group, Advisory Board or similar to bring together a committee that is representative of the customers and their diversity. Use this committee to identify opportunities for the organisation to improve what it does and to test out new ideas.

- Bring a guest speaker to present to the board occasionally – whether it’s a staff member who can talk about their role, or an actual client who is willing to share their story.

- Use technology to record the stories of some clients so that they can be played for the board.

- Use the CEO’s report to the board each meeting as an opportunity to pick a couple of good news stories to highlight the work of frontline staff and impact of the organisation.